Colditz Castle: The Hilarity of Escape

Henry Chancellor delivers a spy-thriller-like account of the Sonderlager Oflag 4C at Colditz Castle, a high-security POW camp for officer prisoners of Allied countries.

I don't get to say this often, but this little speck of WWII history was hilarious.

"Gentlemen, I have a special announcement to make," he said,

"You will understand that I'm a soldier like all of you are and I have my orders to carry out, the same as you have, and I'm carrying out one of those orders now — I hope you'll understand that. I'm not sure if you will like what I'm going to say, but the German government has decided to make a very special offer to officer prisoners of war. Anyone who is a civilian in normal life, who may have some special profession which could be useful to the great German crusade against communism in Europe. . .Volunteer, give your name to me and we'll see what can be done. . .Thank you, gentlemen."

He turned as if to leave, hoping that there weren't going to be brickbats and catcalls; but we were all so astonished that there was silence. And then a Frenchman suddenly clapped to attention and marched forward. The silence intensified. We thought, Well, surely no one's going to volunteer. We were wrong.

"I would like to volunteer," the Frenchman said. Püpcke could hardly speak, he was so astonished. "You mean to say you wish to help us?" "Yes, indeed. And what's more, I hope that you'll give me a maximum amount of work — the more work you give me to do the prouder and happier I shall be." So Püpcke said, "What is your profession? What technical qualifications have you to offer?" "Sir, I am an undertaker."

There was a slight pause and then everyone burst out laughing; there was cheering and clapping, and he was marched away to the cooler [solitary].'

INTRODUCTION

I hadn't heard of Colditz before finding this book in a second-hand bookstore. Apparently, there is quite a legend surrounding it. Knowing what I know now, it makes sense. It's the most audacious and thrilling adventure of human ingenuity I've ever read. The occupants, both prisoner and captor, seemed to have clearly defined roles, like cops and robbers, and the camp atmosphere was filled to the brim with tension seeped in a chase-and-be-chased mentality.

In studying WWII, humor seems inappropriate, but there's something funny about everything. In a recent special, Stand-up comedian Shane Gillis has a great bit about having an interest in WWII - calling it "pre-republican," which is also hilarious. So, to find humor in WWII's hellscape, it has to be passed on.

Henry Chancellor delivers a spy-thriller-like account of the Sonderlager Oflag 4C at Colditz Castle, a high-security POW camp for officer prisoners of Allied countries. Many of the main characters had been inside Colditz since early 1940, with some spending the entirety of the war in German captivity. Many nationalities made up the prisoner population. Polish and Canadian officers were the first to arrive, becoming the welcoming committee to the British, Dutch, French, and Czechs, who were also present. Upon arriving, the inmates were told that "They had shown themselves to be a high-security risk." They were designated a signifying label, Deutschfeindlich — "anti-German." Colditz was the only camp of its kind in Germany, and what sets it apart from other camps, particularly — POW camps — is the potent presence of the Geneva Convention and its (theoretically) binding assurances. These assurances would provide a vastly different camp existence than POWs in the East and the protection needed to mount escapes. When not hammered down by deadly hard labor and the biological desire to survive, you're free to focus on other things, like escaping.

THE CONVENTION

The 1929 Geneva Convention extensively defined the fundamental rights of wartime prisoners, civilians, and military personnel. The central tenet of Article 4 states that officers, upon capture, are only required to provide their name, rank, and DOB. Other Articles included protection from forced labor, torture, and unsanctioned types of punishment. The Convention's third provision made depriving any protected person of these rights a war crime. Germany, The United States, Britain, France, and Japan were all signatories. The absence of the Soviet Union would provide the Nazis with a readied justification for the treatment of Russian POWs during the war. Over 3 million Soviet POWs died in German captivity, and the Soviets brutalized German POWs as forced labor. Japan, a signatory, committed some of the most gruesome atrocities during the war, so simply stamping the country's name on a document did not ensure it would adhere to its principles.

Officers in Colditz did not know how strict their captors would be to the Convention. Overwhelmingly, the Germans ignored the Convention in their treatment of protected groups, most notably civilians in occupied territories. Another Article details the treatment of prisoners and rules on recaptured POWs. When an inmate escaped from Colditz and was recaptured, he could be sentenced to only 28 days of solitary confinement under the provision. The harshest punishment the Germans could enforce. Chancellor describes, "Those are the stakes, but no one knew whether Germany would honor them, nor was it clear what would happen if officers were caught escaping in civilian clothing. Once out of military uniform, an escaper threw away his protection under the Convention and ran the risk of being executed as a spy."

There were guidelines around how many letters the officer could write, protocols for segregating nationalities, and the court-martial process. Most significant were the Red Cross food parcels that began arriving around Christmas 1940. The contents would sustain the soldiers against starvation on multiple occasions, as rations provided to them by the Germans would never be enough. British intelligence also used these to smuggle in tools that would be useful to anyone trying to escape. When the tide of war shifted in 1943, and the Germans were experiencing the fury of Allied bombing, the German infrastructure started to break down, having packages arrive less frequently, forcing officers to ration. The delivery became so sporadic it created famine-like conditions in the camp, and few men had the energy to plan escapes during this time.

"THE CODE"

Chancellor describes "the code" for Western armies upon capture, saying, "If captured, it is the duty of every officer to escape and try to rejoin their country's fighting forces. The code of all Western armies allows for it, and so does the Geneva Convention."

Not everyone in an Oflags wanted to escape, and Chancellor does mention "comfort over the country" to officers who would tamp down on anyone trying to escape as it would upset their comfort in camp. However, most of the book is narratives of engrossing and comedic attempts to escape.

COLDITZ ODDITIES & GLOSSARY

Like most camps, Colditz had a long list of specific characteristics. Among all camps, these characteristics accurately reflect a camp's culture and are used to understand how each camp operates. Colditz had a legendary amount of oddities, insights, and terminology.

In 1933, when Hitler came to power, the castle was transformed into a labor camp for political prisoners. In one of its earlier lives, it had been an asylum in the 1830s. Apart from adding bars to the windows, the castle was never built to keep people in, and this would provide the prisoners ample room to attempt escapes.

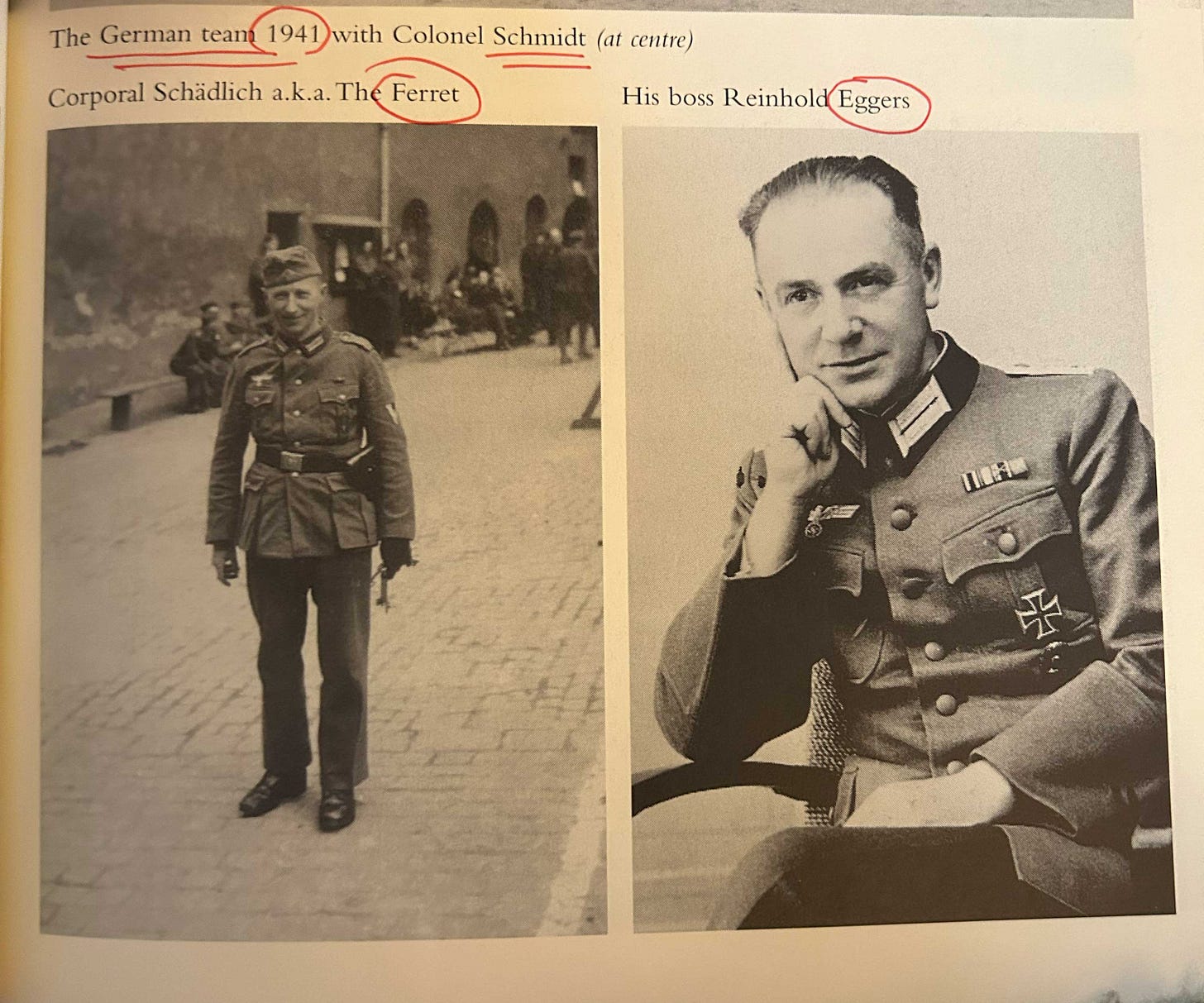

"FERRETS"

The characters within the German guard company had the most impact on the daily lives of their captors. These NCOs were in constant contact with the prisoners. Called 'ferrets,' these types would move abruptly around different prisoner quarters wearing rubber-soled boots, hoping to find anyone engaging in "nefarious activities." Ferrets were often quite successful in their endeavors and remained on the lowest rung of the totem pole to the prisoners.

'GOON-BAITING' & 'STOOGING'

A favorite and consistent pastime for the officers in Colditz was to gnaw down their German guards. This took various forms but was known by one moniker, 'goon-baiting,' and could be specialized to a particular officer to a specific guard. It was a tradition among all nationalities of the Sonderlager, but some seemed more apt to the task than others.

"Locked in a castle hundreds of miles from the theatres of war, the prisoners were engaged in their own private battle: it was known as 'goon-baiting' — annoying the Germans. Goon-baiting was practiced in other camps, but not with the same zeal and frequency as at Colditz."

"There was no reason for it — other than to be a damned nuisance. All twenty-five of us in the French barracks room decided that the next time they had a night-time roll-call, we would have some sport. Normally, they would run up the stairs with their boots and guns clattering and come into the room — a whole group of soldiers and one or two officers. We would stand to attention beside our beds, wearing our pajamas and be counted. So the next night we heard them thundering up the stairs someone shouted, "Everybody take 'em off!" The sad Germans came in as they usually did to find us all stood at attention at the foot of our beds, completely naked. The German soldiers couldn't prevent themselves from laughing — it was completely ridiculous. The officer found himself in a ludicrous situation, and finally, after five minutes, he said: "Let's go". They couldn't take it."

'STOOGING'

Accompanying goon-baiting was 'stooging,' "which operated day and night. Whenever a German entered the yard, the cry of 'goons up' echoed through the quarters. The system depended on a sophisticated set of signals: men spent hours leaning out windows appearing to read or smoke; if they closed their book or took off their cap, it sent a single to another window indicating which staircase the Germans were heading for, and any illicit activity in those quarters promptly ceased."

PAT REID

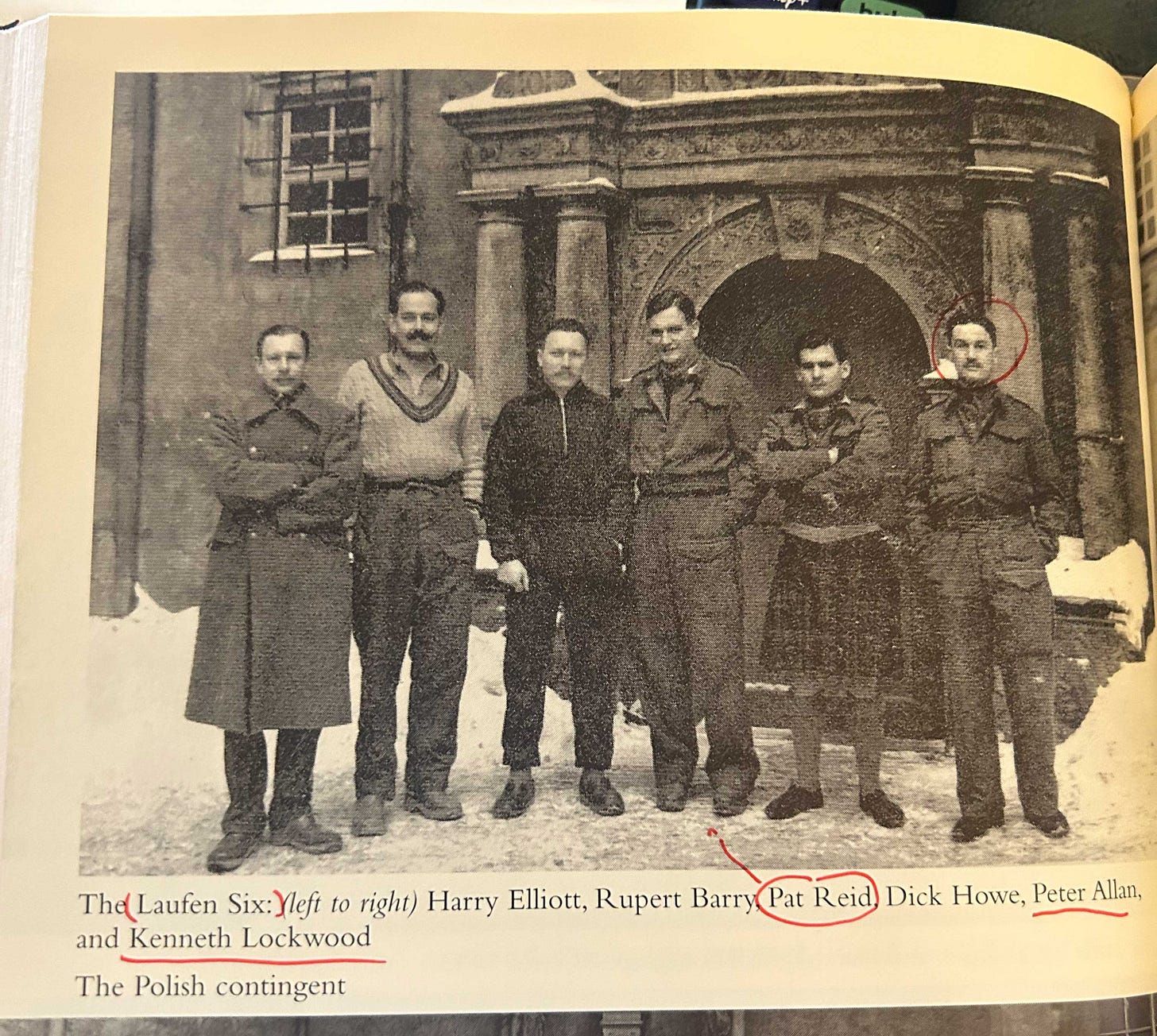

Pat Reid was a captain in the Royal Service Corps who had been captured at Dunkirk in 1940. In civilian life, he was a civil engineer and understood how buildings were constructed, knowledge that would benefit him greatly during his time as a prisoner in Colditz. Reid's book, The Colditz Story, would be the first to construct the legend that became Colditz Castle and the escapes. Reid was part of an infamous group called the "Laufen Six." The moniker was given after the camp, where they made the first British escape from the war. Four of them would spend the entirety of the war in the small confines of the castle.

Pat Reid was on what was known as 'The Escape Committee,' and committee officers were not allowed to escape. In the summer of 1942, Reid masterminded successful escapes for two of his comrades, Frenchman Tony Luteyn and British Airey Neave, and assisted in other planned attempts. Sometime in 1942, Reid was relieved of his duty on the committee, allowing him to attempt his own escape.

"Pat Reid's decision to attempt to escape himself was indicative of the mood of the camp in the summer of 1942. In all, thirty officers attempted to escape during this period, often on consecutive days from different parts of the castle."

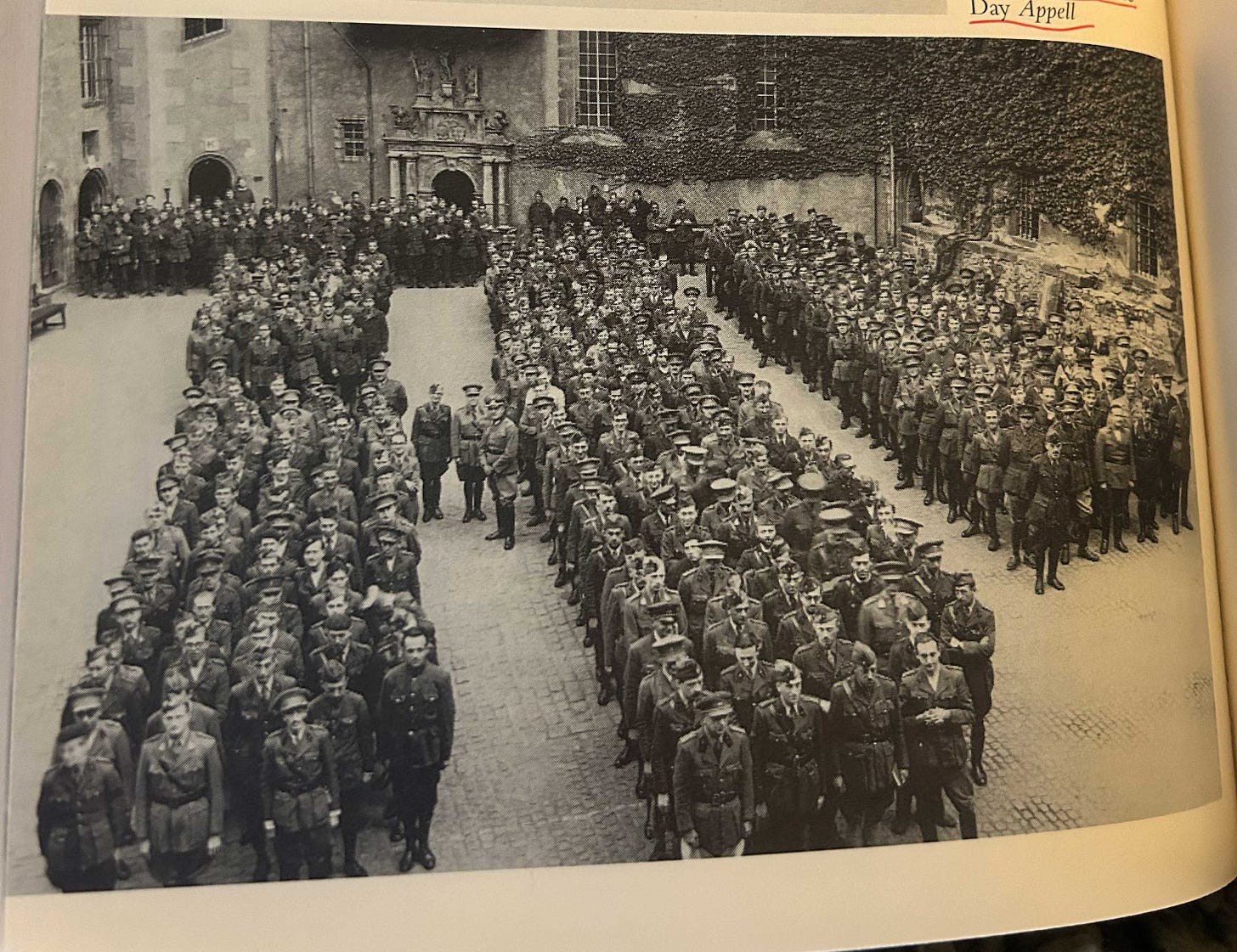

APPELLS / ROLL-CALL

Appells played a significant part in almost all escape attempts, and the ways in which escapers tried to "fudge the count" were of particular genius and equally hilarious. After a failed attempt in December 1941, a Dutch escaper tapped a Pole for help. "Among them [the Poles] was a sculptor who within one week succeeded in making two clay heads who we named "Max" and "Moritz".' The Dutch carried Max and Moritz plus two coats and four boots down to the park to make up the numbers and thereafter they became a regular feature of many nocturnal Appells." "Snap" Appells could be called whenever the Germans felt something afoot.

"As inmates of a Sonderlager, Colditz prisoners were closely watched, and the Germans introduced various measures designed to make their lives more difficult. In other Oflags, there were two Appells (roll-calls) a day; at Colditz were first three, and then four."

'BOY-SCOUTING'

In the early parts of life at Colditz, in 1940, captives used the knowledge they gained about escaping from their time before the war. Most of which was garnered from stories and legends from WWI told in books when they were small boys.

"They hoped to make it ten days, using the time-honored method of 'boy-scouting' described in all classic examples stories of the First World War. Boy-scouting involved sleeping in woods by day and walking by night, avoiding roads, and having minimum contact with the population."

REINHOLD EGGERS, GERMAN SECURITY OFFICE, OFLAG-4

Reinhold Eggers was Colditz's security officer and is steeped in the legend of Colditz Castle. He was the captor of the captives. Eggers was a towering figure within the confines of the Sonderlager. He instituted many new active measures, typically after an escape. He engaged whole-heartedly in the game of cat-and-mouse with his captives. One of Egger's contributions, in 1943, was using passwords and "shift cards" given to each guard at the start of their shift, both changing with every shift. This created another layer of difficulty for the escapers. But it didn't present an insurmountable challenge. It was an addition to the list of things that had to be arranged for a successful escape. One escape in particular was revealed because of these measures. Goon-baiting Eggers was an art form among prisoners, but he refused to show weakness. He viewed the inmates as rowdy schoolboys, and Eggers wouldn't give them the satisfaction of getting to him. In 1941, Eggers "stated that, on average, an escape happened every ten days for all four years of the war."

A former Dutch officer at Colditz wrote the forward in Eggers's book: "This man was our opponent, but nevertheless he earned our respect by his correct attitude, self-control and total lack of rancor despite all the harassment we gave him."

("SNAP") ESCAPES, HOME RUNS AND KITS

When prisoners wanted to escape alone with little to no planning, they often looked for what was called, 'snap escapes.' A snap escape was a quick and dirty opportunity that presented itself in one moment, often lasting only a few minutes or seconds. It was a distracted set of guards or an open gate. It was spontaneous and unorganized, leading the escaper to leave with only what they had on their person and nothing more. As the war progressed and more escape attempts were committed, snap escapes became less frequent as security was beefed up and opportunities diminished. Once outside the castle, having an "escape kit" with you also became imperative to make a "home run."

HOME RUNS & ESCAPE KITS - A FRENCH EXPERIENCE

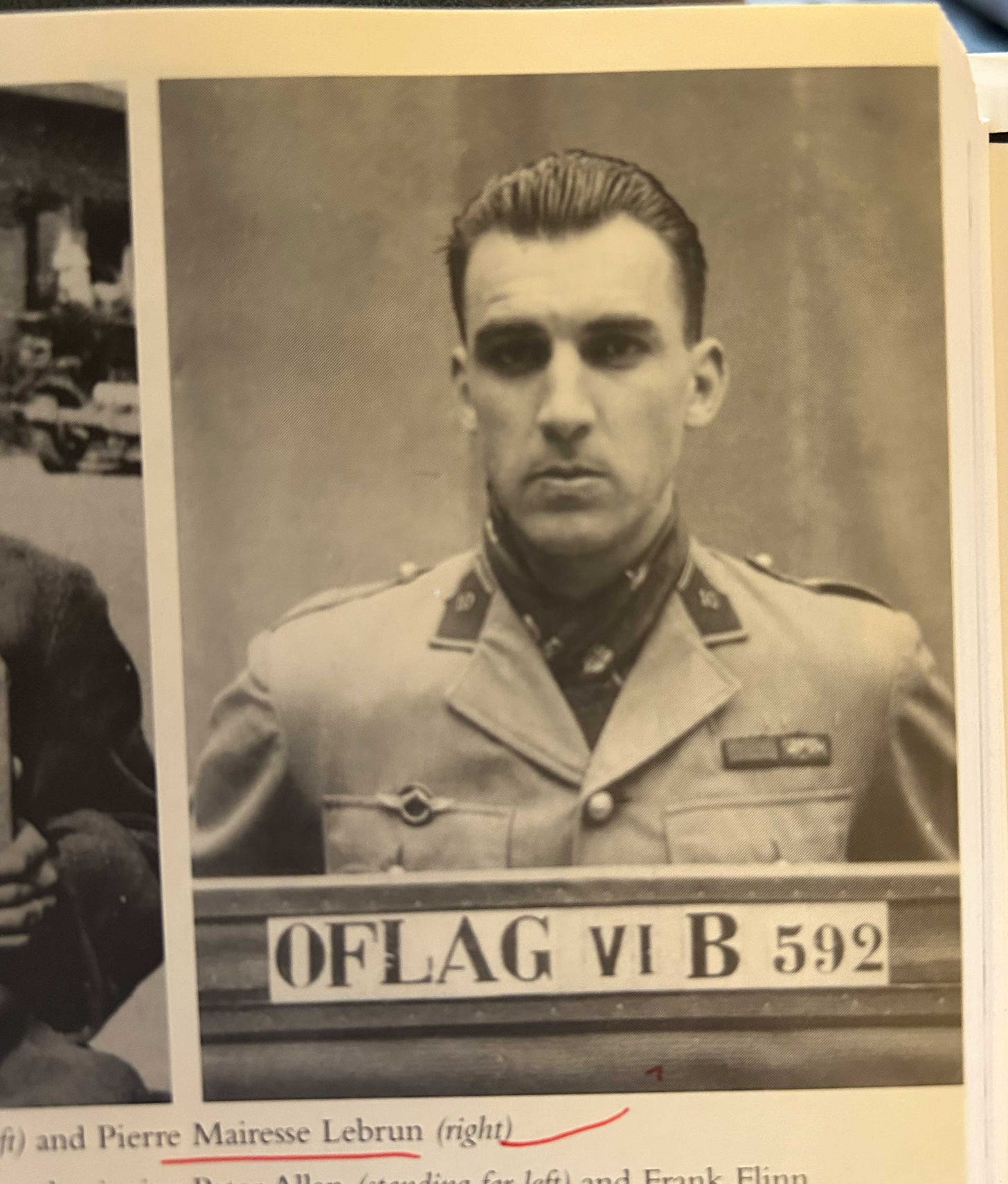

A "home run" was a successful escape from enemy territory. In the early days of 1940, a home run was reaching Switzerland — a 400-mile journey out of Germany without being noticed or recaptured. Pierre Mairesse Lebrun was a French cavalry officer captured during the Fall of France; he attempted many escapes from the Colditz, but one was more audacious and successful than any other. In Lebrun's "escape kit," he had a pair of shorts, a scarf, and other clothing. He had sewn sugar packets, chocolates, a razor, and a bar of soap into the scarf.

"Lebrun's plan was audacious to the point of stupidity; using a comrade as a springboard, he would vault over the wire fence and run for the park wall. He knew the guards would fire at him, but it was a calculated risk. 'I think it's easy to be brave in war unless you are a complete coward. Escaping is a voluntary act of bravery, which is very difficult. Very difficult when you are risking your life. During other escapes, I had never risked my life as directly as I intended to now.'"

As night fell, Lebrun decided to leave the woods and began walking, evading German patrols looking for him. Once out of the immediate area, he walked through the rain for three days to Zwickau, seventy miles south of Colditz. The sugar and chocolates sustained him, and he even managed to get cake and beer without ration coupons. Passing by an unlocked bicycle leaning against a wall, he casually strode away, pedaling as fast as his legs would take him. Setting off southwest to Nuremberg, he hoped to reach the Swiss border in four days. Upon entering the city of Ulm, the bicycle's front tire split open; undeterred, he still rode the next 50 miles on just the rim. After eight days out of Colditz, he got to Singen, leaving the bicycle in the woods. After night fell, he was sent out on foot toward Switzerland, but without a map, he was still determining where exactly he was and how much further he needed to go. Lebrun was walking through the woods alone when he spotted a young girl. As he appeared and showed himself to the girl, and in his best German, he said: "Don't be afraid, I'm a French escapee, a French officer." The girl appeared to understand him. Lebrun went on to ask, "Am I in Switzerland or Germany?" and she said: "But, monsieur, I am Swiss; you are in Switzerland!"

Lebrun had made a home run.

"When news of Lebrun's escape reached Colditz, his portrait was hung in the French quarters and decorated with the tricolor ribbon; and his leap of freedom soon came to be regarded by all POWs incarcerated in Germany as one of the greatest escapes of the war.

Even Reinhold Eggers was forced to agree. 'For sheer mad and calculated daring, the successful escape of the calvary lieutenant, Pierre Mairesse Lebrun, will not, I think, ever be beaten.'"

DANGERS BEYOND THE CASTLE / THE HITLER YOUTH

One of the greatest dangers for those who had successfully escaped from both inside and outside the castle was the Hitler Youth..

"If an escaper managed to slip through this net he faced the daunting task of crossing Germany. Colditz Castle stood in the heart of Saxony, four hundred miles from the nearest neutral frontier, and in 1941 the boundaries of Hilter's Greater Germany were still expanding. Once 'out' the greatest threat often came from the eager and inquisitive Hitler Youth. "We couldn't give a damn about old men and women," recalls the French escaper Pierre Mairesse Lebrun. "But these Hitler Youth characters had only one thing on their minds. They were twelve, fourteen years old, and they all wanted to become heroes by catching an escaped prisoner. They reported anyone acting suspiciously and they were given money if they found someone. You needed a lot of luck to avoid them."

THE ESCAPE COMMITTEE

By July 1941, the castle was filled to the brim with prisoners and escape plans. A few uncoordinated attempts contradicting each other led to the need for a governing body known as The Escape Committee.

"This incident ushered in the international escape committee. Each nationality would appoint an Escape Officer, responsible for telling his counterparts about any attempts that were planned and when they were intended to take place. Each Escape Officer was privy to other nations' secrets, but there was a caveat; Escape Officers were not allowed to escape."

COLDITZ ESCAPE MUSEMUM

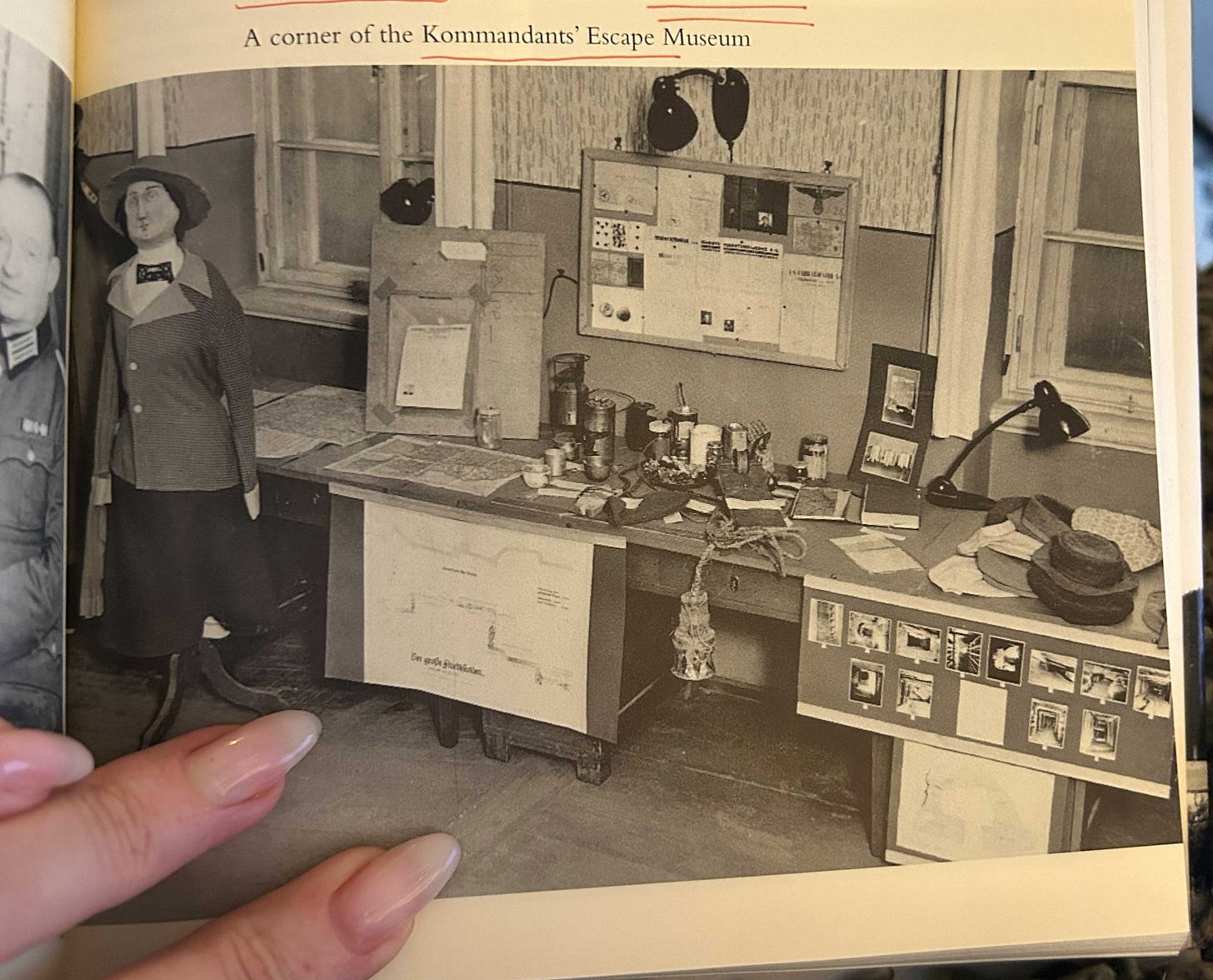

Max and Moritz were included in what became known as the "Escape Museum." Various elements used in escapes would be added throughout the war. Accompanying Max and Moritz were compasses hidden in walnuts that British Intelligence smuggled in and fake papers forged made inside the castle.

"By now the Germans had acquired so much escape equipment they an unofficial museum in the Kommandantur, which displayed every captured article. Among key exhibits were the photographs of Johannes Lange, a local man who was drafted in to record every detail of escapes. Officers posed in their home-made clothes, tunnels, and ropes were photographed in situ, and escapers were even made to re-enact their escapes."

UNMENTIONED ELEMENTS

There are too many elements of life at the Colditz Castle to explain in a single post. Some of these unmentioned insights are below, and only a few of the many others are present in this story.

'Dotty' Codes

"It was a classic example of communication via a 'dotty' code — so-called because the punctuation provided the clue as to how to read it. Dotty codes were in use between many officers and their families during the course of the war. Official sources encouraged their use in certain circumstances, though they felt they should not be used to transmit vital information — they were too easy to decipher."

MI9's "Naughty Kits"

"To be prepared for escape, soldiers, sailors, and in particular, airmen had to carry three essentials into combat: a map, a compass, and enough food to see them safely home. Each item had to be disguised, for they would be searched when they were captured. If an immediate escape was not possible, MI9 planned to help by sending tools and equipment into POW camps. What MI9 needed was nothing less than a magician — a man with an ability to conceal escape aids within everyday objects which could be delivered to prisoners by the post."

"Clay Hutton had been a pilot in the First World War, and had gone on to work in public relations in the film industry. He could see extraordinary potential in ordinary things — an ability he shared with many of the men from who he was designing escape aids. He began by making compasses, maps, and food parcels. His compasses were hidden inside a pen or the button of a tunic..."Clutty" found other hiding places for compasses, too, such as bars of soap and walnuts."

"MI9's operations created a small industry in 1941 and 1942: as many as 1,642 'naughty' parcels were dispatched to POW camps in Germany, all with Clayton Hutton's escape equipment hidden in their contents."

"Arse Creepers"

'Pat Reid had some cigars sent to him by some university friends, recalls Kenneth Lockwood [one of the Laufen Six]. They all arrived in their cases, each in a little cylinder with a screw top. They were Upmann cigars. The name gave us the clue as to how to secrete our false papers and money. They became known as "arse creepers".'

WASPS

"Bill's idea was that, since leaflets were being dropped by the RAF all over Germany, it was up to us to play our part. Hundreds of wasps were caught and to each was attached a cigarette paper with the message, Deutschland Kaput. The French, never to be outdone, caught a large number of wasps, tied a little square paper to each, put them in matchboxes and released them together on parade. It was like a reversed snowstorn with the wasps flying upwards in furious mood. Pandemonium raged with all of us warding off the angry wasps, or pretending to."

Histories collide

It's not often that histories collide, but it feels like magic when they do. Airey Neave was a British Officer sent to Colditz in 1941. He would go on to perform an audacious escape, earning one of the few home runs that the British experienced in Colditz. He was the first British officer to make a home run from Colditz. While reading Patrick Radden Keefe's book about the IRA and the Troubles in Northern Ireland, I learned that Neave would go on to be made head of Margaret Thatcher's private office. He was assassinated in 1979 by an IRA car bomb planted in London.

"Like many Dutchmen before him, Tony Luteyn had memorized Hans Larive's route to the Ramsen salient from Singen. Despite getting lost in the snow, the escapers avoided the border patrols and ever-inquisitive Hitler Youth to cross the frontier into Switzerland forty-eight hours later. Airey Neave had achieved the first British home run."

CONCLUSION:

Reading about the prisoners of the Sonderlager at Colditz Castle was an odd palette cleasner after my last few read on Auschwitz and the Einstazgruppen. The legend and participants, both captors and captives, had quite a unique experience in comparison to other aspects of the war and other POW camps. Colditz's security apparatus grew tighter and tighter as the war progressed and the tides changed. Eggers remained at his post until Allied forces arrested him in April of 1945. After, "Reinhold Eggers returned to the life of a schoolmaster, but in September 1946 he was arrested and sentenced under Russian law to ten years' hard labor on the charge of supporting a fascist regmine. He was released in 1956, and then with some ceremony he was flown over to England by the inveterate goon-baiter Douglas Bader, who surprised both his friends and Eggers by becoming his former gaoler's greatest champion. Eggers even arrived as a special guest for Pat Reid's This Is Your Life in 1974."

The book carries you through various escape plots, attempts, failures, and home runs. Each one is seemingly more impossible or stupid than the last. Chancellor instills hope in every one, and you start to believe that this might actually work, until it doesn't. Riding the rollercoaster could barely prepare you for how the story ends and how the British contingent experiences liberation and freedom. The legend of Pat Reid, the Laufen Six, Pierre Lebrun, Airey Neave, Mike Sinclar, and many others is a history that provides detailed and unknown chapters of bravery, comradeship, collaboration, and human ingenuity.

KG 2023